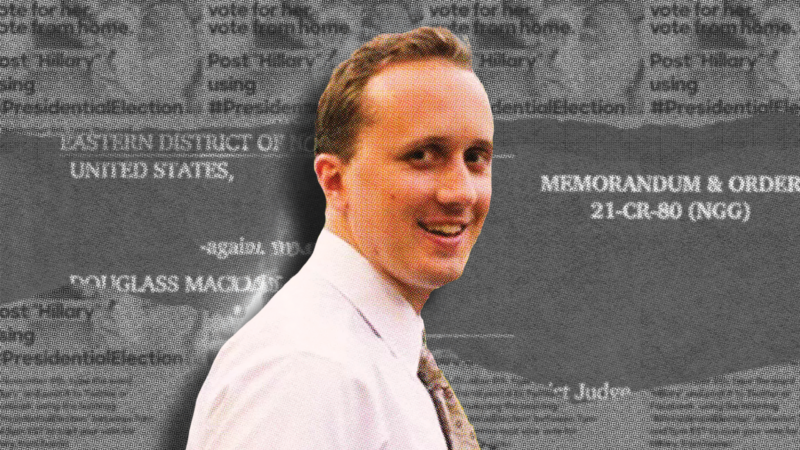

He's Going to Prison for Twitter Trolling. That's Not Justice.

Douglass Mackey's case raised questions about free speech, overcriminalization, and a politicized criminal legal system.

It took an FBI investigation, a three-week trial, and lots of taxpayer dollars, but the government finally got what it wanted this week: A Florida man is heading to federal prison for disseminating trollish memes during the 2016 election season that prosecutors alleged "deprive[d] people of their constitutional right to vote."

In the months leading up to Election Day, Douglass Mackey, an erstwhile far-right social media influencer, posted a series of photos on his Twitter profile—which had about 58,000 followers under the name "Ricky Vaughn"—encouraging Hillary Clinton–supporters to cast their votes by phone. That obviously didn't go so well for the people who fell for it. But however you feel about Mackey's obnoxious brand of politics and feeble attempt at comedy, the case became about a lot more than him, raising questions about protected speech, overcriminalization, and a politicized Department of Justice.

To prosecute Mackey, the government leveraged a law from 1870, a century and change before Twitter trolling would become a sport. That legislation was passed to deter the Ku Klux Klan from trying to prevent black people from voting, as they were known to do. According to the indictment, the DOJ alleged Mackey conspired to "injure, oppress, threaten and intimidate one or more persons in the free exercise and enjoyment of a right and privilege secured to them by the Constitution and laws of the United States, to wit: the right to vote."

It seems fairly clear that Mackey did not "threaten" or "intimidate" social media users. Whether he "injure[d]" or "oppresse[d]" them is perhaps more nebulous, but it is certainly not what lawmakers intended to address with the Enforcement Act when it was passed 153 years ago. The most notorious image Mackey posted was that of a black woman standing in front of an "African Americans for Hillary" sign, with the caption "Avoid the line. Vote from Home" and "Text 'Hillary' to 59925." At least 4,900 people texted that number, according to the DOJ. That's not nothing, but it can also be stated with a fair degree of conviction that his stupid scheme had no material impact on former President Donald Trump ultimately clinching office.

A jury convicted him in March of this year. This week, Judge Ann M. Donnelly of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York sentenced him to seven months in prison, calling his behavior "nothing short of an assault on our democracy."

Perhaps most curious about Mackey's prosecution, and the many resources poured into it, is that he is not the only person to have executed such a ruse. On the morning of November 8, 2016—Election Day—the comedian Kristina Wong tweeted a video of herself decked out in Trump's signature "Make America Great Again" red baseball cap, sitting in front of "Make America Great Again" yard signs, encouraging a familiar, yet inverted, refrain. "I just want to remind all my fellow Chinese Americans for Trump, people of color for Trump, to vote," she said. "Vote for Trump."

The video came with a caption: "Skip poll lines at #Election2016 and TEXT in your vote!" Wong said. "Text votes are legit. Or vote tomorrow on Super Wednesday!"

Wong has not faced criminal charges, nor should she. The thought of the FBI devoting time to investigating her for a silly tweet is ludicrous and an insult to the taxpayers that fund the agency. The notion that she'd spend time in prison for it defies parody. And yet there is someone whose reality is exactly that.

"Evidence showed that participants discussed generating interest in emails stolen from the Clinton campaign by Russia; portraying Mrs. Clinton as a 'warmonger'; and promoting the claim that she had 'cheated' during the primaries to get supporters of Senator Bernie Sanders to 'hate not just Hillary, but the Democratic Party itself,'" reported The New York Times. People of varying political persuasions will disagree with some, or all, of those tactics. But they are views that were (and still are) commonly held not only on the right but also among much of the political left. That they qualified as "evidence" of criminal liability does not speak well of the government's case against Mackey.

How his prosecution may impact free speech rights generally remains to be seen. There are already limited exceptions to the First Amendment, like defamation and libel. But as Eugene Volokh, a professor at UCLA School of Law, points out, there is no Supreme Court jurisprudence and no laws that specifically address the legality of what Mackey (and Wong) did. Perhaps there should be. But if the government wants to prosecute someone, they should do so based on what the law is—not what they wished it to be.

Show Comments (256)