The War on Sex Trafficking Is the New War on Drugs

And the results will be just as disastrous, for "perpetrators" and "victims" alike.

"Sex Trafficking of Americans: The Girls Next Door."

"Sex-trafficking sweep nets arrests near Phoenix truck stops."

"Man becomes 1st jailed under new human trafficking law."

Conduct a Google news search for the word trafficking in 2015 and you'll find pages of stories about the commercial sex trade, in which hundreds of thousands of U.S. women and children are supposedly trapped by coercion or force.

A few decades prior, a survey of "trafficking" headlines would have yielded much different results. Back then, newspapers recounted tales of "contemporary Al Capones trafficking illegal drugs to the smallest villages and towns in our heartland," and of organized "motorcycle gangs" trafficking LSD and hashish. "Many young black men in the ghetto see the drug trade as the Gold Rush of the 1980s," the Philadelphia Inquirer told readers in 1988. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) warned of a "nationwide phenomenon" of drug lords abducting young people to force them into the drug trade. Crack kingpins were rumored to target runaways, beating them if they didn't make drug sales quotas.

Such articles offered a breathless sense that the drug trade was booming, irresistible to criminals, and in desperate need of child foot soldiers. Lawmakers touted harsher penalties for drug offenses. The war on drugs raged. New task forces were created. Civilians were trained how to "spot" drug traffickers in the wild, and students instructed how to rat out drug-using parents. Politicians spoke of a drug "epidemic" overtaking America, its urgency obviously grounds for anything we could throw its way.

We know now how that all worked out.

The tactics employed to "get tough" on drugs ended up entangling millions in the criminal justice system, sanctioning increasingly intrusive and violent policing practices, worsening tensions between law enforcement and marginalized communities, and degrading the constitutional rights of all Americans. Yet even as the drug war's failures and costs become more apparent, the Land of the Free is enthusiastically repeating the same mistakes when it comes to sex trafficking. This new "epidemic" inspires the same panicked rhetoric and punitive policies the war on drugs did—often for activity that's every bit as victimless.

Forcing others into sex or any sort of labor is abhorrent, and it deserves to be treated like the serious violation it is. But the activity now targeted under anti-trafficking efforts includes everything from offering or soliciting paid sex, to living with a sex worker, to running a classified advertising website.

What's more, these new laws aren't organic responses by legislators in the face of an uptick in human trafficking activity or inadequate current statutes. They are in large part the result of a decades-long anti-prostitution crusade from Christian "abolitionists" and anti-sex feminists, pushed along by officials who know a good political opportunity when they see it and by media that never met a moral panic they didn't like.

The fire is fueled by federal money, which sends police departments and activist groups into a grant-grubbing frenzy. The anti-trafficking movement is "just one big federal grant program," Michael Hudson, a scholar with the conservative Hudson Institute, told the Las Vegas Review-Journal. "Everybody is more worried about where they're going to get their next grant" than helping victims, Hudson said.

Because of the visceral feelings that the issue of paid sex has always provoked, it's easy for overstatements and false statistics to go unchallenged, winning repetition in congressional hearings and the press. Yet despite all the dire proclamations, there's little evidence of anything approaching an "epidemic" of sexual slavery.

THE NUMBERS DON'T ADD UP

From 2000 to 2002, the State Department claimed that 50,000 people were trafficked into the U.S. each year for forced sex or labor. By 2003, the agency reduced this estimate to 18,000–20,000, further reducing it to 14,500–17,500 in subsequent reports. That's a 71 percent decrease in just five years, though officials offered no explanation as to how they arrived at these numbers or what accounted for the drastic change. These days, federal agencies tend to stick to the vague "thousands" when discussing numbers of incoming victims.

Globally, some 600,000 to 800,000 people are trafficked across international borders each year, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) estimates. But the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 2006 described this figure as "questionable" due to "methodological weaknesses, gaps in data, and numerical discrepancies," including the rather astonishing fact that "the U.S. government's estimate was developed by one person who did not document all his work." And even if he had, there would still be good reasons to doubt the quality of the data, which were compiled from a range of nonprofits, governments, and international organizations, all of which use different definitions of "trafficking."

Glenn Kessler, The Washington Post's "Fact Checker" columnist, began digging into government-promulgated sex-slavery numbers last spring and discovered just how dubious many of them are. "Because sex trafficking is considered horrific, politicians appear willing to cite the flimsiest and most poorly researched statistics—and the media is content to treat the claims as solid facts," Kessler concluded in June.

For instance, Rep. Joyce Beatty (D–Ohio) declared in a May statement that "in the U.S., some 300,000 children are at risk each year for commercial sexual exploitation." Rep. Ann Wagner (R–Mo.) made a similar statement that month at a congressional hearing, claiming the statistic came from the Department of Justice (DOJ). The New York Times has also attributed this number to the DOJ, while Fox News raised the number to 400,000 and sourced it to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). But not only are these not DOJ or HHS figures, they're based on 1990s data published in a non-peer-reviewed paper that the primary researcher, Richard Estes, no longer endorses. The authors of that study came up with their number by speculating that certain situations—i.e., living in public housing, being a runaway, having foreign parents—place minors at risk of potential exploitation by sex traffickers. They then simply counted up the number of kids in those situations. To make a bad measure worse, anyone who fell into more than one category was counted multiple times.

"PLEASE DO NOT CITE THESE NUMBERS," wrote Michelle Stransky and David Finkelhor of the respected Crimes Against Children Research Center in 2008. "The reality is that we do not currently know how many juveniles are involved in prostitution. Scientifically credible estimates do not exist." A lengthy 2013 report on child sex trafficking from the Justice Department concluded that "no reliable national estimate exists of the incidence or prevalence of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States."

Common sense should preclude believing the 300,000 number in the first place. If even a third of those "at risk" youth were peddled for sex in a given year, we'd be looking at nearly 110,000 victims. And since advocates often claim that victims are forced to have sex with 10, 20, or 30 clients a day, that would be—using the lowest number—1.1 million commercial child rapes in America each day. Even if we assume that child rapists are typically repeat customers, averaging one assault per week, that would still mean nearly 8 million Americans have a robust and ongoing child rape habit, in addition to the alleged millions who pay for sex with adults.

Common sense should also immediately cast doubt on another frequently cited statistic: that the average age at which females become victims of sex trafficking is 13. "If you think about it for half a minute, this statistic makes little sense," wrote Kessler. "After all, if it is the 'average,' then for all those who entered trafficking at age 16 or 17, there have to be nearly equivalent numbers who entered at age 9 or 10. But no one seriously believes that."

Still, the obvious implausibility of the statistic—and its routine debunking—hasn't stopped it from reaching the upper echelons of public discourse. Kessler's own Washington Post ran it uncritically in 2014. Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D–Minn.) made the claim on the Senate floor this year, citing the FBI. The DHS also asserts that "the average age a child is trafficked into the commercial sex trade is between 11 and 14 years old," sourcing it to the DOJ and the government's NCMEC. Yet none of these federal agencies take responsibility for this stat. When Kessler followed the facts down the rabbit hole, the original source in all cases was…the self-disowned Estes paper, in which interviews with 107 teens doing street-based prostitution in the 1990s determined that their average age of entry into the business was 13.

"So one government agency appears to cite two other government entities—but in the end the source of the data is the same discredited and out-of-date academic paper," wrote Kessler. "It would be amusing if it were not so sad."

Author and former sex worker Maggie McNeill has traced other uses of the age-13 figure back to a similarly narrow and unrepresentative study, this one looking at underage streetwalkers in 1982 San Francisco ("Victimization of Street Prostitutes" by M.H. Silbert and A.M. Pines). Among these interview subjects from three decades ago, the average age of their first noncommercial sexual experience was 13. The average age of entry into prostitution was 16, and the report made no mention of sex trafficking at all.

Surveys of adults working in the U.S. sex trade have yielded much higher average starting ages. A 2014 Urban Institute study involving 38 sex workers found that only four began before age 15, 10 started between the ages of 15 and 17, another four started in their 30s, and the remaining 20 began sex work between the ages of 18 and 29. A 2011 study, this one from Arizona State University, found that of more than 400 women arrested for prostitution in Phoenix, the average age of entry was about 25.

"Regardless of whether the number is 300,000 or 30,000, something must be done to protect these children at risk of exploitation and trafficking," said Moira Bagley Smith, a spokeswoman for Rep. Wagner, when Kessler challenged the figure. But it's exactly this kind of thinking that inflicts real-world policy damage. Whether there are 30,000 or 300,000 crime victims makes a great deal of difference in terms of fashioning an appropriate response, as does the context of the victims' circumstances. Separating the mythology of sex trafficking from the facts is crucial for addressing problems as they exist, not problems as we might want, fear, or imagine them to be.

WILLFUL HYPERBOLE

A 2010 study from Rutgers University professors James Finckenauer and Ko-lin Chin took an in-depth look at Chinese women working in America's illicit massage parlors, which are routinely denounced by politicians as hotbeds of sexual slavery. Indeed, Finckenauer noted that 93 percent of the women he interviewed would be considered sex trafficking victims under common legal definitions, which include any person who arrives in a foreign country for sex work regardless of whether force or coercion is involved. Yet not one of the 149 Chinese women interviewed said she was sold into prostitution, and only one reported being forced or coerced into it. "There is more diversity among the parties involved in prostitution than is commonly supposed, and to portray them all in the same way as victims is an oversimplification," the researchers concluded.

Under federal law and most state laws, anyone under 18 who is engaged in prostitution is considered a sex trafficking victim. But study after study has found most youths in the sex trade do not have "pimps." And if they are forced or coerced into the work, it's often at the hands of a family member or romantic partner, not some child-snatching stranger.

Pimps themselves claim to steer clear of underage sex workers. In interviews with 73 people who had been incarcerated for crimes such as promoting, profiting from, or compelling prostitution, the Urban Institute found that most tried to avoid business relationships with teens (though these respondents, along with the police officers Urban interviewed, also claimed it was common for teenagers to lie about their ages). "I was determined to stay away from the younger bitches; 16 gets you 20," said one respondent. "Bitch better have a felony charge and stretch marks to mess with me," said another. "I know she is grown and been to jail."

"This particular business ain't about pimps going to high school and recruiting a girl," said a third. "Government don't understand how this game original come about. Girl run away from home, look older than what she is. They think pimps are going out and enticing them."

By any estimation, teen runaways make up a major proportion of underage individuals in prostitution, forced or otherwise. Runaways are especially likely to engage in what sociologists call "survival sex"—exchanging sex not for a set fee, but for food and a place to crash.

Sixty-eight percent of minors engaged in street-based prostitution in New York City say they've sought help from youth services organizations, according to Kate D'Adamo of the Sex Workers Project. "New York City funds roughly 200 beds for a population of 4,000 unaccompanied, homeless youth," D'Adamo told TechCrunch. "When all the beds are full, it is street economies like the sex trade which they turn to in order to provide basic needs. If we want to identify the most vulnerable, all we have to do is provide support when someone stands up and says 'I need a place to sleep tonight.'"

Instead, we fund police task forces to monitor Internet ads for weeks in search of suspect code words or tattoos. We pass laws mandating more prison time for pimps. We set up elaborate sting operations for both sex workers and their customers. We hang "Are you being trafficked?" signs at strip clubs and highway rest stops, and train airport staff on how they can spot the signs of sex trafficking. We act as if sex traffickers are organized, jet-setting, diabolical, and legion. We are chasing our own mythology, to the detriment of actual results.

A look at human trafficking investigations in the U.S. makes this clear. In July 2015, for instance, Homeland Security, the Arizona Department of Public Safety, and other Arizona state agencies conducted a joint "human trafficking enforcement operation" that involved randomly stopping commercial trucks as well as running the license plates of passersby. The 30-agent, nine-hour stunt resulted in 28 stops, the checking of 5,576 license plates…and zero arrests for human trafficking. Police did arrest one woman for prostitution, however, and are continuing to investigate another who said she worked in "adult entertainment."

Last April, the FBI released its first crime data on state-based trafficking investigations. In the 13 states reporting for last year, law enforcement looked into a total of 14 human trafficking incidents, ultimately making a grand total of four arrests.

Between 2008 and 2010, federally funded task forces investigated 2,515 suspected incidents of human trafficking, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. An "investigation" was defined as "any effort in which the task force spent at least one hour investigating" the incident. Of these cases, only 6 percent led to arrests. From 2007 to fall 2008, federal dollars funded 38 sex-trafficking task forces, of which 15 found no confirmed victims or suspects, 14 reported between one and four cases, and nine reported more than five. Of the total 1,229 suspected incidents that year, sex cops found just 14 underage victims.

"Given the obstacles to locating victims in black markets" some disparity between estimated numbers and confirmed cases should be expected, wrote the sociologist Ronald Weitzer in a 2011 Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology paper. But "a huge disparity between the two should at least raise questions about the alleged scale of victimization."

UNNECESSARY LEGISLATION

Of all the myths and misinformation about sex trafficking in America, the most pernicious may be that our current laws are insufficient. Pushing his new Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act, which passed last May, Sen. John Cornyn (R–Texas) declared that it would "provide law enforcement with the tools" to hold human traffickers accountable. Another co-sponsor, Sen. Mark Kirk (R–Ill.), said the bill "gives police and prosecutors the tools they need to go after sex traffickers." Such statements—and there are plenty more—imply that we currently lack tough anti-trafficking laws. Yet for at least 15 years, federal policy makers and agencies have been continually strengthening these laws and increasing funding for their enforcement.

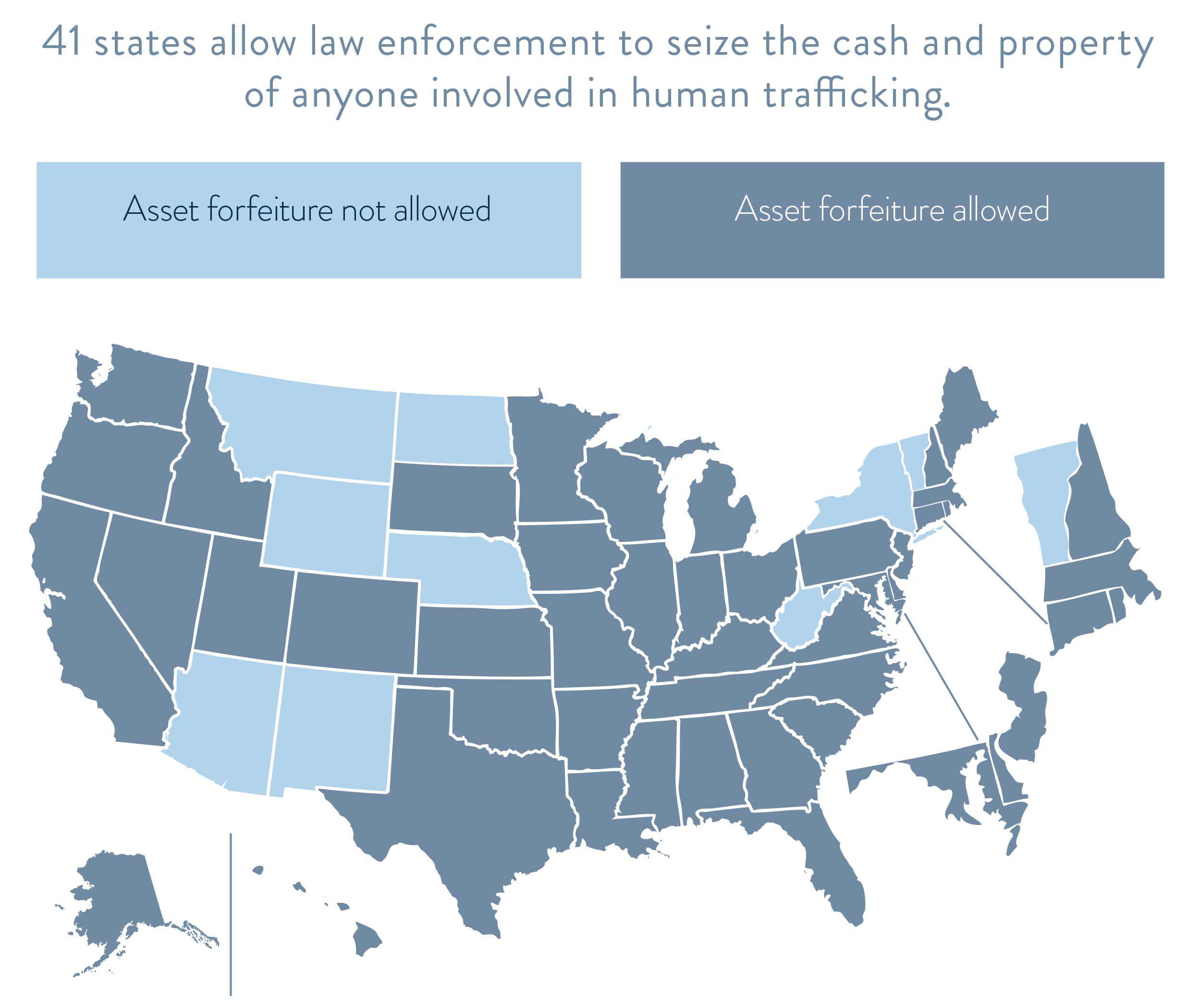

Things really got going with the passage of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) in 2000, though before this federal agents could bring human trafficking charges under various statutes, including the Mann Act (passed in 1910 to prohibit transporting a minor across state lines for the purposes of engaging in prostitution), the Tariff Act (passed in 1930 to ban importing goods made with forced or indentured labor), and various laws related to peonage, indentured servitude, and slavery. But the TVPA, signed by President Bill Clinton in the waning days of his presidency, specifically established as federal crimes "forced labor," "sex trafficking," and "unlawful conduct with respect to documents in furtherance of trafficking." It also created a national Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, and gave the feds authority to seize traffickers' assets.

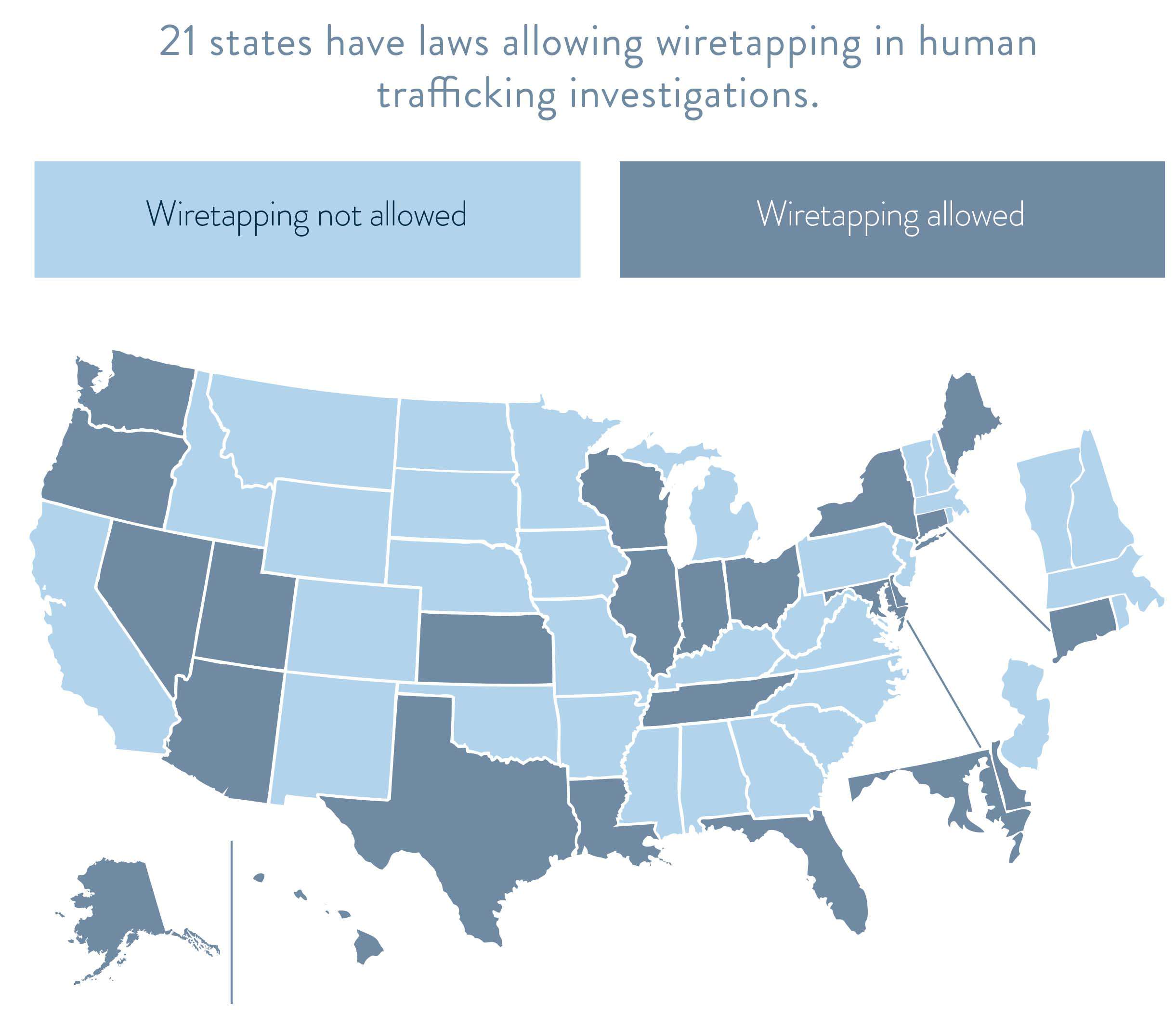

The TVPA's 2003 reauthorization gave law enforcement the ability to use wiretapping to investigate sex trafficking and child sexual exploitation, increased the minimum and maximum sentencing requirements for a variety of sex offenses, and instituted a "two strikes, you're out" rule requiring mandatory life imprisonment upon a second sex offense involving a minor, "unless the sentence of death is imposed." The 2005 reauthorization added human trafficking to crimes that can trigger the federal Racketeer Influenced Corrupt Organizations (RICO) law, expanded asset forfeiture possibilities, and directed the CIA to study "the interrelationship between trafficking in persons and terrorism." It also increased funding for the prosecution of "persons who engage in the purchase of commercial sex acts."

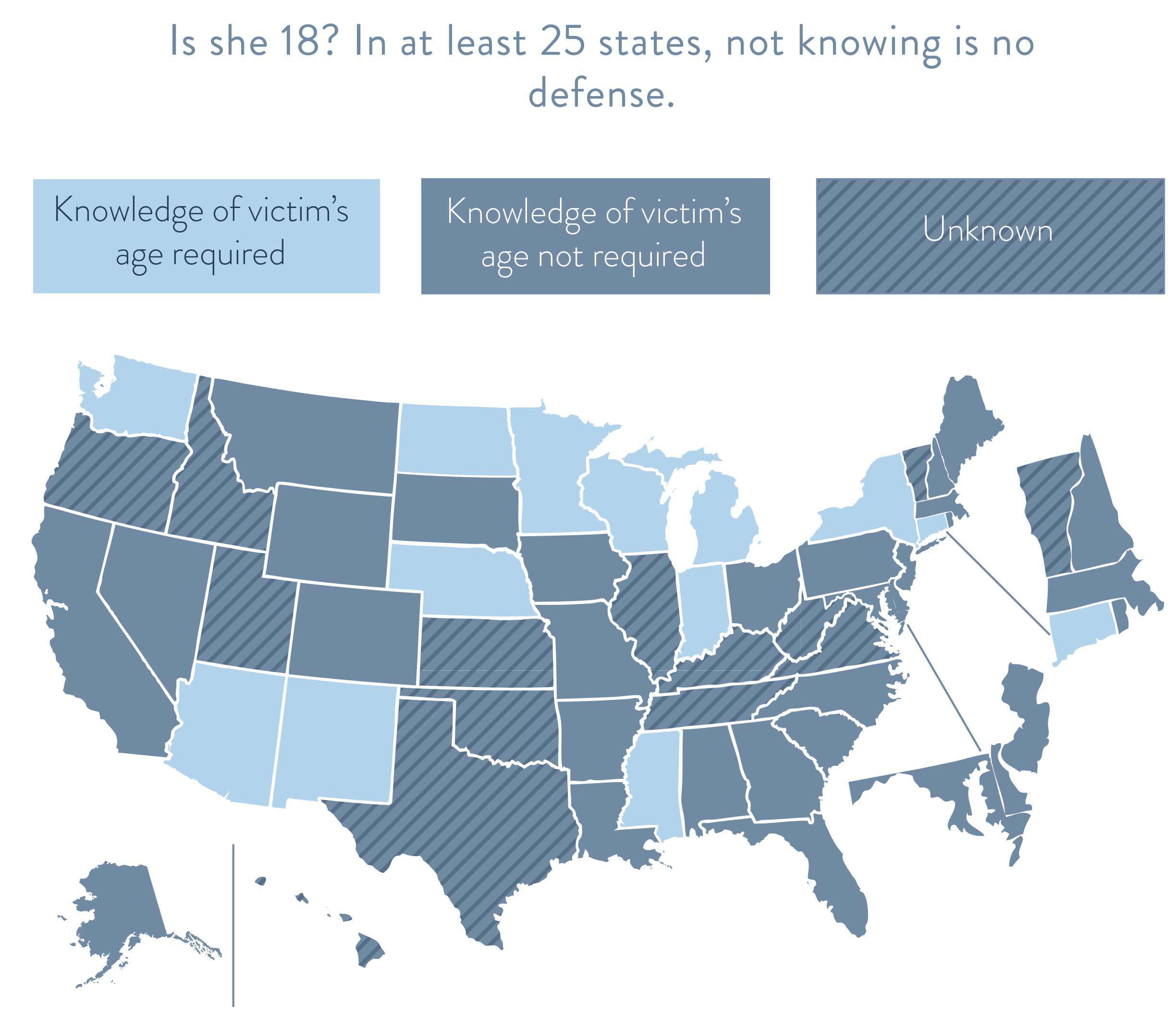

In 2008, legislators enhanced criminal penalties for human trafficking and expanded what qualifies to include several new areas, including anyone who "obstructs, attempts to obstruct, or in any way interferes with or prevents the enforcement of" anti-trafficking laws. It specified that in minor sex trafficking cases, "The Government need not prove that the defendant knew that the person had not attained the age of 18 years." And it significantly increased federal funding—doubling some appropriations and more than tripling others—for anti-trafficking efforts at home and abroad. The 2013 reauthorization increased federal involvement with state and local anti-trafficking efforts.

This year's Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act made soliciting paid sex from a minor a form of federal sex trafficking; established a Domestic Trafficking Victims' Fund into which anyone convicted of trafficking must pay $5,000; and lowered the evidentiary standard for proving trafficking charges. The act also established that websites and publishers—from classified ad sites such as Craigslist to social media services such as Twitter and Reddit—may be charged with sex trafficking if any victim is found to have advertised there. And it created a "HERO corps" of military veterans who will work with Immigrations and Customs Enforcement agents to fight cybercrime, including "digital intellectual property theft" and "hidden marketplaces."

Sen. Cornyn called it a "first step."

The State Department's 2014 Trafficking in Persons report states explicitly that our current penalties for human trafficking "are sufficiently stringent and commensurate with penalties prescribed for other serious offenses." Penalties for forced labor, involuntary servitude, or peonage range from five to 20 years without aggravating factors; possible life imprisonment with them. Sex traffickers can receive up to life imprisonment, and are required to serve at least 10 years in prison if the victim is under 17 and 15 years if the victim is under 14. Victims may also independently file a civil cause of action; something 117 have done since 2003, with a 75 percent success rate.

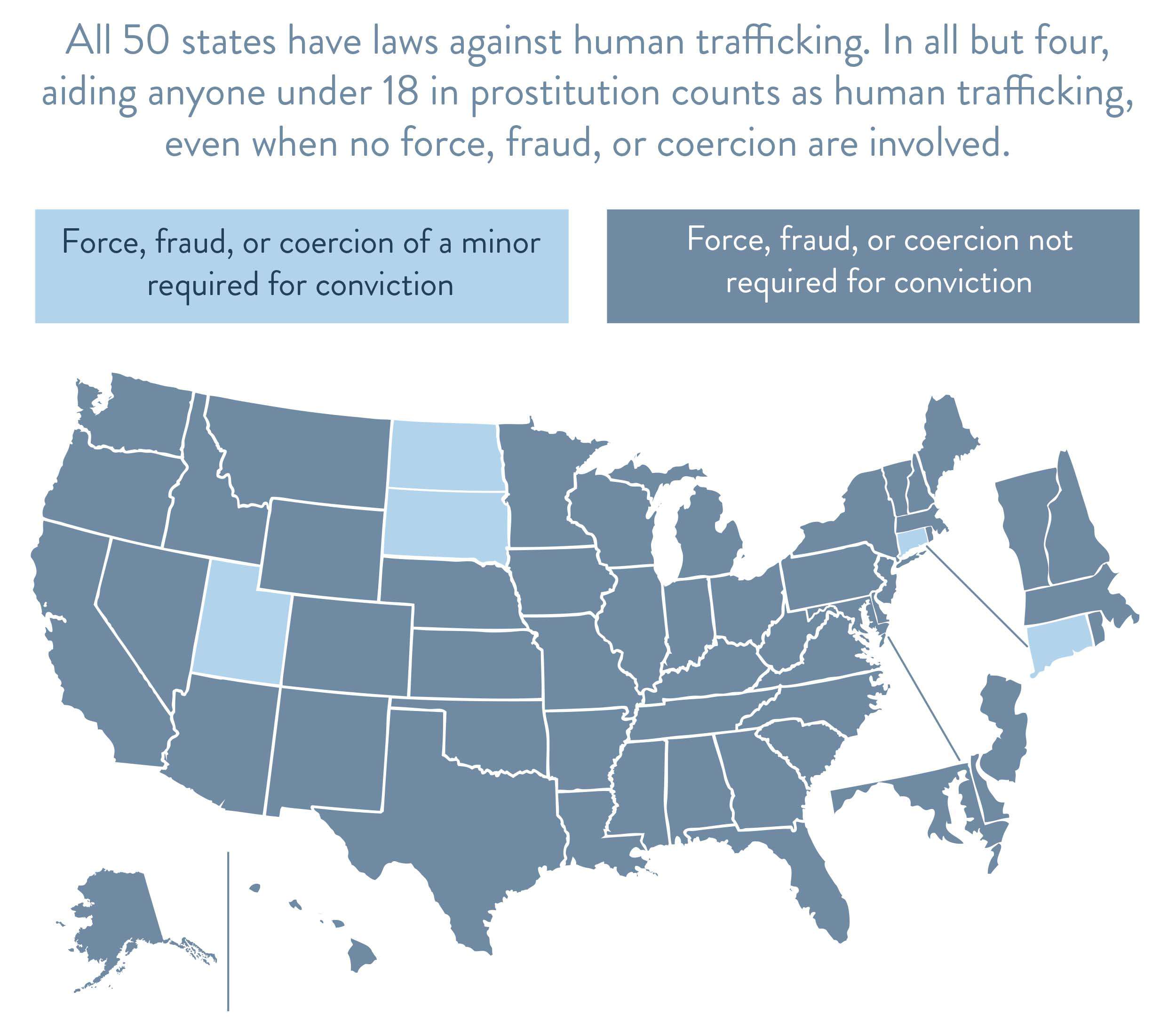

In addition to federal anti-trafficking laws, states have been adopting a flurry of their own measures. In 2014 alone, 31 states passed new laws concerning human trafficking. Since the start of 2015, at least 22 states have done so.

Echoing the policy choices of the drug war, one common trend in these laws has been harsher sentences for trafficking offenses, including new mandatory minimums. In Florida, helping a minor engage in prostitution in any way now comes with mandatory life imprisonment. In Louisiana, labor trafficking of a minor comes with a five-year mandatory minimum, and sex trafficking of a minor 15 years. In New Jersey, soliciting a minor for paid sex comes with a minimum $15,000 fine. Some states have also started adding "aggravating" factors that trigger higher penalties, such as the offense taking place within a certain distance of a school or group home.

Another trend is adding trafficking-related offenses to those that get perps on sex-offender registries. Last January, Arkansas passed a bill requiring anyone convicted of trafficking in persons or "patronizing a victim of human trafficking" to register as a sex offender. Increasing criminal penalties on patrons, or "johns," has been hot in state legislatures, too.

In 21 states, "sex trafficking laws have been amended or originally enacted with the intent to decisively reach the action of buyers of sex," according to the anti-trafficking nonprofit Shared Hope International. In 2014, Michigan changed soliciting someone under 18 for sex from a misdemeanor to a felony sex offense. Florida recently stipulated that people found guilty of soliciting prostitution (from someone of any age) must do 100 hours of community service and attend "john school," where they will be educated on "the negative effects of prostitution and human trafficking."

Expanding police/prosecutorial power to fight and profit from trafficking is also common. At least 21 states now allow police to use wiretapping in trafficking investigations. And many states allow asset forfeiture for those convicted of sex trafficking or prostitution. For instance, in Colorado, "every building or part of a building including the ground upon which it is situated and all fixtures and contents thereof, every vehicle, and any real property" are up for grabs if they've been used in conjunction with prostitution of any kind.

The final category of popular new state laws seems predominantly concerned with "raising awareness," be it via classes for hotel employees, programs in school curricula, or signs posted in strip clubs. Dozens of states now require certain entities—from adult-entertainment businesses and job-placement firms to hospitals, rest stops, and airports—to post the National Human Trafficking Hotline number, or face penalties. In Georgia, failure to do so can result in fines of between $500 and $5,000.

Federal agencies are also in the trafficking publicity game. In July 2015, the DHS announced the expansion of "awareness efforts to major airports, truck stops, and motorist gas stations across the country," where it will fund messages describing "the signs of human trafficking" on signs, video monitors, and shopping bags. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission conducted more than 250 human trafficking "outreach events" in 2013 alone.

REFRAMING PROSTITUTION

If there's no empirical evidence that domestic human trafficking is increasing, and the State Department says we already have adequate laws to go after traffickers, then what's driving this current legislative frenzy?

One factor is opposition to prostitution, even between consenting adults. Since the 1990s, a coalition of Christian and radical feminist activists has been working to redefine all prostitution as sex trafficking. While the Clinton administration was unsympathetic to their efforts, they found a friend in President George W. Bush. In a 2002 National Security Presidential Directive, the White House stated that prostitution was "inherently harmful and dehumanizing." Hence the administration's new rule: Non-governmental organizations receiving federal funds to fight human trafficking (or AIDS) must explicitly oppose prostitution.

"Prostitution is not the oldest profession, but the oldest form of oppression," a State Department publication from 2004 reads. The agency stated that "the vast majority of women in prostitution don't want to be there," that "few activities are as brutal and damaging to people as prostitution," and that "prostitution leaves women and children physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually devastated," with damage that "can never be undone."

"Since the early 2000s, anti-prostitution policies at the federal level have translated into increasingly aggressive state and local-level policing of sex workers and their customers," wrote Kari Lerum, Kiesha McCurtis, Penelope Saunders, and Stephanie Wahab in a 2012 article for Anti-Trafficking Review. This conflation of trafficking and prostitution "has allowed for federal dollars to be used locally for anti-prostitution purposes," the authors noted. "Anti-trafficking raids, such as Operation Cross Country held annually since 2006, have resulted in the arrest of many sex workers nationwide using federal anti-trafficking dollars."

The goal of Operation Cross Country, according to the FBI's website, is "to recover victims of child sex trafficking." In 2014, more than a dozen cities took part. Knoxville, Tennessee, to cite one participant, uncovered zero underage victims of sex trafficking, but it did arrest eight women for prostitution, four women for promoting prostitution, two women for human trafficking, and four men for solicitation. In Newark, New Jersey, one 14-year-old victim was identified and 45 people were arrested for prostitution or pimping. Richmond, Virginia, found no child victims but charged 26 people with prostitution and two with pimping. In Atlanta, dozens were arrested for prostitution, loitering, soliciting, and drug possession.

Phoenix officials announced the most victims recovered: five minors and 42 adults. But dig beyond the press release and you'll see the adult "victims" included women willingly working in prostitution. Officers posing as clients answered these women's online ads and then apprehended them. One 20-year-old "victim" had her arm broken by the cops when she tried to flee. A 16-year-old victim was booked on prostitution charges when she refused to let officers contact her parents. After failing to secure emergency shelter for two adult victims who had no money and no identification, police returned them to the motel where they'd been apprehended "so they could try and arrange funds to get back" home.

INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF A MORAL CRUSADE

In a 2012 paper published in Politics & Society, Ronald Weitzer suggested that the 1990s anti-prostitution crusade has become fully "institutionalized" in the 21st century. "Institutionalization by the state may be limited or extensive—ranging from consultation with activists, inclusion of leaders in the policy process, material support for crusade organizations, official endorsement of crusade ideology, resource mobilization, and the creation of legislation and new agencies to address the problem," Weitzer wrote. Sound familiar?

"Some moral crusades are so successful that they see their ideology fully incorporated in government policy and vigorous efforts by state agencies to combat the problem on their own," he noted. In other words, "the movement's central goals become a project of the government."

It's hard to think of a better representative of this institutionalization than the Polaris Project, one of America's biggest anti-trafficking groups. Founded by a man who now runs the website Everyday Feminism and a woman who now works for the federal government, Polaris has drafted multi-pronged model legislation for the taking. Compare Polaris' recommendations with state trafficking laws, and you'll find near verbatim language in some, and shared assumptions and goals in almost all.

How did Polaris gain such influence? One way is through state "report cards." Advertised as a measure of states' commitment to fighting human trafficking, it's basically a measure of how closely their laws hew to the Polaris policy wishlist. Among the must-haves: a law requiring the display of the national human trafficking hotline number, which Polaris runs with funding from Health and Human Services. States that fail to enact all of the Polaris-endorsed policies wind up with bad grades, which the organization then publicizes extensively.

Another driver of state trafficking policies is the Uniform Law Commission (ULC), a nonpartisan organization that drafts model state legislation in a variety of areas. In 2010, ULC was asked by the American Bar Association to prepare a plan for tackling human trafficking. The result was drafted in collaboration with Polaris, Shared Hope International, the National Association of Attorneys General, and the U.S. State Department, then approved by the bar association in 2013.

In the first half of 2015, two states enacted laws based on ULC's model legislation and four others introduced them. Four states enacted ULC-based trafficking laws in 2014 with 10 more attempting to. Among the model legislation's main tenets are court-ordered forfeiture of real and personal property for traffickers, providing "immunity to minors who are human trafficking victims and commit prostitution or nonviolent offenses," and imposing "felony-level punishment when the defendant offers anything of value to engage in commercial sexual activity."

That last bit is part of what's known as the "end-demand" strategy, or the "Nordic model," which focuses heavier penalties on sex buyers than sex sellers. Popularized by Nordic feminists, it's since become the law of the land in Canada and is rapidly influencing American policy, with many religious-based anti-trafficking groups also adopting its rallying cry. As a result, cities and states around the country have begun increasing penalties for prostitution clients and rebranding them as sexual predators. In Seattle, for instance, the crime of "patronizing a prostitute" was recently rechristened "sexual exploitation."

The theory behind "end demand" is that if only we arrest enough patrons or make the punishments for them severe enough, people will stop trying to purchase sex. Voila! No more prostitution, no more sex trafficking. If that sounds familiar, perhaps you're old enough to remember the '80s, when a similar approach was supposed to bring down the drug trade.

"Ending the demand for drugs is how, in the end, we will win," President Ronald Reagan declared in 1988. Indeed, it was how we were already winning: "The tide of the battle has turned, and we're beginning to win the crusade for a drug-free America," Reagan claimed.

In reality, the number of illicit drug users in America has only risen since then, despite the billions of dollars spent and hundreds of thousands of people locked away. In 1990, for instance, 7.1 percent of Americans had used some sort of illegal drug in the past month, according to the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. By 2002 it had risen to 8.3 percent, and by 2013 to 9.4 percent.

The utter failure to "end demand" for drugs hasn't dented optimism that we can accomplish the trick with prostitution. During the "National Day of John Arrests" each year, police pose as sex workers online and then arrest would-be clients. Each year, hundreds of men are booked in these stings and charged with offenses ranging from public indecency and solicitation to pimping and sex trafficking. If these anti-trafficking efforts sound a lot like old vice policing, that's because the tactics, and results, are nearly identical.

In a study released last year by Shared Hope International and Arizona State University, researchers examined end-demand efforts in four metro areas over a four-month period. Between 50 and 60 percent of these efforts involved police decoys pretending to be teens, and no actual victims. A typical tactic is for police to post an ad pretending to be a young adult sex worker, and once a man agrees to meet, the "girl" indicates that she's actually only 16 or 17.

Shared Hope is candid about the fact that most of the men soliciting sex here are not pedophiles and not necessarily seeking out someone underage. But "distinguishing between demand for commercial sex acts with an adult and demand for commercial sex acts with a minor is often an artificial construct," its report asserted. So to save the children, we need to prosecute men who have no demonstrated interest in children, because in the future they may seek sex with adults who could actually turn out to be old-looking teens—got that?

"One shortcoming of the reverse sting approach is that no live victims are rescued from trafficking," Shared Hope admitted. "But it does take intended perpetrators of child sex trafficking off the Internet and off the streets."

Bipartisan Paranoia

A federal war on prostitution doesn't play well with large segments of Americans. Fighting human trafficking, on the other hand, is a feel-good cause. At a 2012 Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) speech, President Barack Obama insisted that we must call human trafficking "by its true name—modern slavery." And what kind of monster would be against ending slavery? Which brings us to another factor driving all this trafficking action: It makes politicians look good.

At a time when Republicans and Democrats can barely agree on anything, human trafficking bills have attracted huge bipartisan support. Here is an area where enterprising legislators can attach their names to something likely to pass. And if it doesn't pass, for whatever reason, it's ripe for demagoguery: "My opponent voted against a bill to fight modern slavery!" Tough-on-crime policies, particularly tough-on-drugs policies, used this tactic for decades, until mass incarceration finally lost its luster.

Undoubtedly, many lawmakers do legitimately want to help trafficking victims and hold bad guys accountable; political point-scoring is just a happy side effect. But a less happy side effect is a slew of bad laws, violated rights, and squandered money. The federal government has given away scores of millions in grant dollars for this quixotic crusade.

The resources spent on prostitution stings and public awareness campaigns are resources diverted from mundane but more effective strategies for helping at-risk youth, such as adding more beds at emergency shelters. The State Department's latest Trafficking in Persons report notes that "shelter and housing for all trafficking victims, especially male and labor trafficking victims, continue to be insufficient." Advocates routinely say the biggest barrier to escape for many trafficking victims is simply a lack of places to go.

"Studies focused on New York City consistently report that homeless youth often trade sex for a place to stay each night because of the absence of available shelter beds," noted the Urban Institute in a report last year. "These figures are even more striking for LGBTQ youth…According to a survey of nearly 1,000 homeless youth in New York City, young men were three times more likely than young women to have traded sex for a place to stay, and LGBTQ youth were seven times more likely than heterosexual youth to have done so. Transgender youth in New York City have been found eight times more likely than non-transgender youth to trade sex for a safe place to stay."

What's more, many of the policies in place to fight trafficking actively work against their own stated mission. The criminalization of prostitution keeps sex workers from reporting abuse and keeps clients from coming forward if they suspect someone is being trafficked. Victims themselves are afraid to go to police for fear they'll be arrested for prostitution—and indeed, they often are.

In 2012, 579 minors were reported to the federal government as having been arrested for prostitution and commercialized vice. Prosecutors say they need this as a "bargaining chip" to make the victims testify against their perpetrators. We're just using state violence and the threat of incarceration against children in order to save them!

Another misguided government target is the classified advertising website Backpage, home to many an "escort" ad. Lawmakers accuse the site of "profiting off of child exploitation," even though only a miniscule percentage of Backpage ads—which anyone can put up—are posted by traffickers rather than adult sex workers. Both legislators and anti-trafficking groups have long been intent on shutting the site down. Yet "street-based sex workers, across studies, face much higher rates of violence than indoor sex workers," says Serpent Libertine, a Sex Workers Outreach Project (SWOP)-Chicago board member. "It's hard to understand how eliminating a low-barrier way to work indoors would promote safety."

Vera Lamarr, also with SWOP-Chicago, pointed out that Backpage cooperates with law enforcement in the U.S. more than many other sites do. "It's hard to understand the desire to take down a website that voluntarily supports efforts against trafficking and willingly cooperates with law enforcement," Lamarr says. "If Backpage closes, their user base could easily migrate to a less cooperative site" or be forced back out on the streets, where traffickers don't leave digital records.

But at least we're getting the really bad guys, right? That's also up for debate. Peruse trafficking arrest records and you'll find many folks like Amber Batt, an Alaska woman who faces 10 to 25 years in federal prison (plus a lifetime on the sex-offender registry) for running an escort service featuring adult women who freely elected to work there. Or Julie Haner, a 19-year-old Oregon sex worker who was charged with trafficking after taking her 17-year-old friend with her to meet clients. Or Aimee Hart, 42, who served seven months in prison and faces 15 years on the sex-offender registry for driving her adult friend to a prostitution job. Or Hortencia Medeles-Arguello, a 71-year-old Houston bar owner arrested as the leader of a "sex trafficking conspiracy" because she allowed prostitution upstairs.

There's Trenton McLemore, 29, who faces federal sex trafficking charges for "facilitating" the sex work of his 16-year-old girlfriend by purchasing the girl a cellphone and sometimes texting clients for her. He faces a mandatory minimum of 10 years and possible life in prison, thanks to a joint effort of Irving, Texas, police; Homeland Security; and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. And Alfonso Kee Peterson, 28, arrested in July for telling a 17-year-old on Facebook that he could help her earn a lot of money from prostitution. The "teen" turned out to be a police decoy. Despite the absence of any real victim or any activity beyond speech, Peterson was charged with one felony count of human trafficking of a minor, one felony count of pandering, and one felony count of attempted pimping; he faces up to 12 years in prison. This important sting apparently warranted the work of several local police departments, the California Highway Patrol, and the FBI.

Even if we grant that some of this activity is unsavory, is it really the sort of behavior that warrants lengthy prison sentences and attention from federal agents? Since when is what adults—or even teenagers—willingly do with their genitalia a matter of homeland security? Is this really what President Obama had in mind at the CGI conference when he compared anti-trafficking laws to the Emancipation Proclamation?

"To be sure, linking trafficking and slavery could, in theory, surface important similarities between political economies of chattel slavery (largely) of the past, and modern-day trafficking," the American University law professor Janie Chuang wrote in a paper published in the American Journal of International Law last year. "Drawing out such nuanced comparisons is not, however, the current trajectory of slavery creep. Instead, this version promotes an understanding of trafficking as a problem created and sustained by individual deviant actors, and thus best addressed through aggressive crime control measures."

For a fraction of the money spent on these measures, state governments or private foundations could fund more beds at emergency shelters. The resources that churches, charities, and radical feminists use trying to convince people that all sex workers are victims (and their clients predators) could go toward helping that minority of sex workers who do feel trapped in prostitution with job placement or getting an education. For the vast majority of vulnerable sex workers, the greatest barriers to exit aren't ankle-cuffs, isolation, and shadowy kidnappers with guns, but a lack of money, transportation, identification, or other practical things. Is helping with this stuff not sexy enough? As it stands, many of those "rescued" by police or abolitionist groups find that their self-appointed saviors can't actually offer them housing, food, a job, or anything else of urgent value in starting a life outside the sex trade. Awareness doesn't pay the bills.

Kamylla's story typifies this rescue paradox. A Texas mother who had fallen on hard times after an injury ended her construction career, she started working in prostitution last year. One day, producers from the A&E television series 8 Minutes contacted her, having seen her ad on Backpage. Though 8 Minutes was marketed as a reality show where a rogue pastor found and "saved" sex trafficking victims in real time, Kamylla and others (who were selling sexual services willingly, even if their situation wasn't optimal) actually talked with producers several times beforehand. The show promised to help with her overdue rent and finding a job, she says. After filming, they gave her $150 and told her they'd be in touch soon about further assistance.

They never called. When Kamylla followed up, the producers referred her to the same unhelpful social services she'd already tried on her own. Eventually Kamylla returned to Backpage, posting an ad using the same phone number that the producers had used to contact her. The first call she received was from an undercover cop, who arranged to meet her and another sex worker at a motel. Once the women agreed to oral sex for money, "he opened the door and nine police officers came inside the room," she says. Both women were taken to jail and booked on prostitution charges.

In a world with no gray areas—one where traffickers are always evil predators and victims always utterly helpless, where sex workers are never ambivalently engaged with their work, and the bright line between teendom and adulthood is always apparent and meaningful—in this world, the raid-and-rescue model of addressing sex trafficking may make some sense. You don't give a girl chained to a bed a condom and call it a day.

But in the world as it exists, sometimes a 17-year-old runaway chooses prostitution because it's better than living in an abusive foster home. Sometimes a sex worker gives all her money to a man because she loves him or thinks she needs him, or that he needs her. Sometimes a struggling mother doesn't love the sex trade, but finds it the best option to feed her kids. Sometimes an immigrant would rather give hand jobs to strangers than face whatever drove her to leave her own country. Harm reduction strategies like handing out condoms in popular prostitution areas, offering STD tests, or even just facilitating online advertising (rather than street work) could prove lifesaving to these women.

Yet when it comes to the way we talk about commercial sex, you have to be a victim or a predator. We've created a narrative with no room for nuance. We traffic not in facts but in melodrama. In TV broadcasts, campus panels, and congressional hearings, the most lurid and sensational stories are held up as representative. Legislators assure us that their intent is noble and pure.

But remember: Tough-on-drugs legislation was never crafted or advertised as a means to send poor people to prison for life over a few grams of weed. It was a way to crack down on drug kingpins, violent gang leaders, evil crack fiends, and all those who would lure innocent children into addiction, doom, and death. Yet in mandating more police attention for drug crimes, giving law enforcement new technological tools and military gear with which to fight it, and adding ever-stricter prison sentences and punishments for drug offenders, we unleashed a corrupt, authoritarian, biased, and fiscally untenable mess on American cities without any success in decreasing drug rates or the violence and danger surrounding an activity that human beings stubbornly refuse to give up.

Unless we can learn the lessons of our past failed crusades, the war on sex trafficking could result in every bit as much misery as its panicky predecessors. Here's hoping it won't take us another four decades to realize that this prohibition doesn't work either.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The War on Sex Trafficking Is the New War on Drugs."

Show Comments (77)